Implementing The AAP/EFP Periodontal Classification System

The 2017 world workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant diseases set out to update the existing periodontal classification system to align with our current understanding of periodontal disease and conditions. The updated classification system amended diagnostic gaps by introducing specific case definitions for periodontal health1 and peri-implant diseases and conditions.2 It also simplified the diagnosis of periodontal diseases by grouping “aggressive periodontitis” and “chronic periodontitis” under the single diagnostic umbrella of “periodontitis.”3 The most notable change with the new periodontal classification system was the introduction of a multidimensional Staging and Grading system used to describe periodontitis.

"The most notable change with the new periodontal classification system was the introduction of a multidimensional Staging and Grading system"

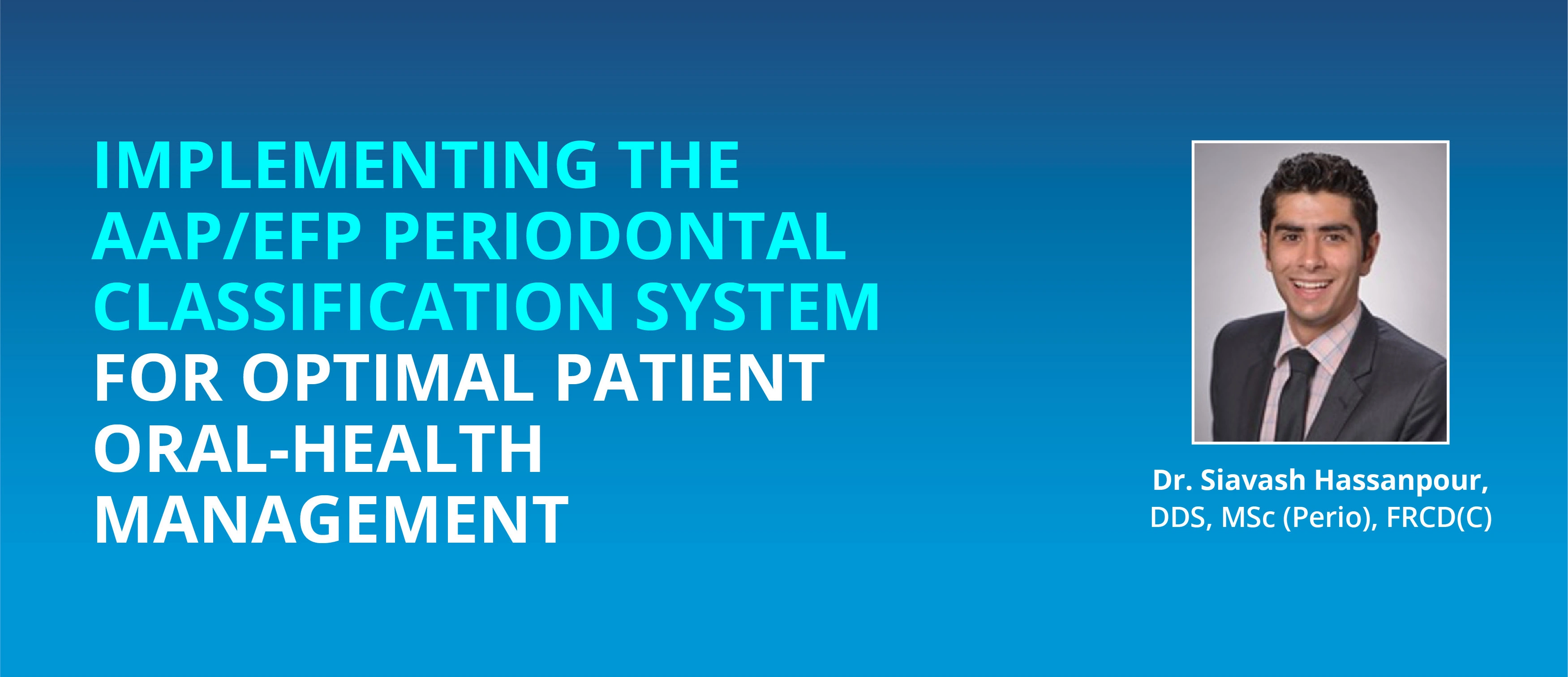

Staging is a 4-tiered severity system (1 to 4) with each tier representing a more severe form of the disease. Simply put, Staging determines the severity and complexity of the disease based on clinical and radiographic parameters. Grading, on the other hand, is a 3-tiered risk system that uses history-based analysis of rate of disease progression and the presence of known periodontal risk factors (such as plaque control, smoking status, and glycemic control) to determine the rate of future disease progression and predict the outcome to targeted treatment.4

Compartmentalizing the AAP/EFP Classification System for Effective Diagnosis

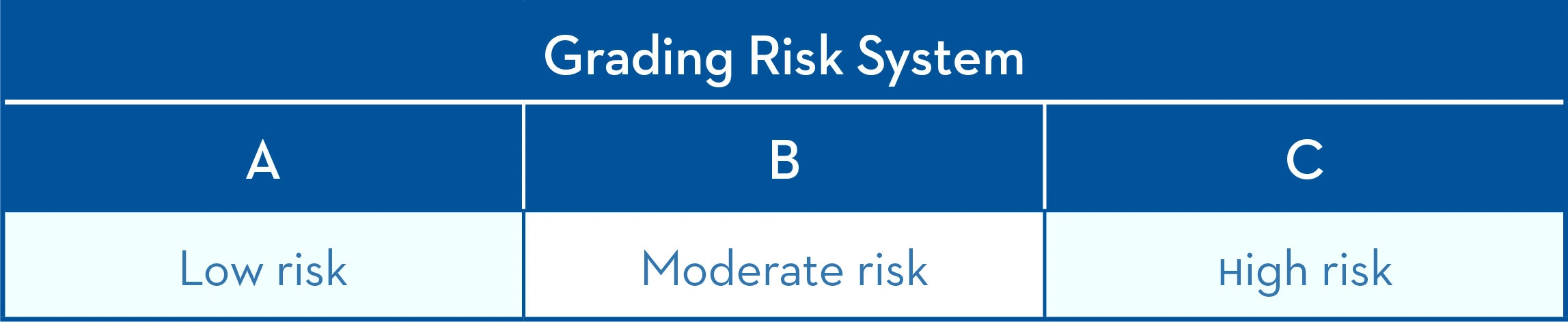

Anytime a substantial change is made to a long-standing diagnostic scheme, clinical adoption will be challenging, and those hoping to incorporate the new system into their daily practice may be faced with uncertainty and confusion when trying to identify the various disease states. As a practising periodontist and a clinical instructor at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Dentistry, I have found it helpful to compartmentalize the classification system into the four most common diagnostic criteria.

Clinical periodontal health is defined by the absence of or presence of very low levels of clinical inflammation within the periodontium. A clinical healthy periodontium is characterized by <10% bleeding on probing, no signs of active periodontal disease (probing depths <4mm), no radiographic signs of bone loss and controlled modifying and predisposing factors (Figure 1).5

In the absence of ideal plaque control, an ecological shift occurs within the plaque biofilm from a healthy microbiome to a pathogenic biofilm. The accumulation of pathogenic biofilm without mechanical disruption will develop into plaque induced gingivitis that is characterized by clinical signs of inflammation on a stable periodontium with no signs of bone loss.

The onset of periodontitis is represented by attachment loss and bone loss. Periodontitis is a progressive, chronic, irreversible disease state that without recognition and treatment will culminate in tooth loss. Stage I and II periodontitis represent the early forms of the disease that are amenable to non-invasive or minimally invasive treatment. On the other hand, Stage III and IV periodontitis represent advanced forms of the disease that will require surgical intervention and often require advanced multidisciplinary management (Figure 2).7

Regardless of the diagnostic state, a prescribed home-care regimen that is individualized, safe and effective is a key part of the treatment of periodontal disease and maintenance of periodontal health. For this reason, the entire dental team (including the patient) must appreciate that periodontal disease is not a simple bacterial infection but rather a complex disease with a complex pathogenesis that involves an interplay between oral microbiome, the host’s inflammatory response as well as genetic, environmental, and behavioural modifying factors.8

" a prescribed home-care regimen that is individualized, safe and effective is a key part of the treatment of periodontal disease"

We have all observed how patient non-compliance and poor home-care practices can exacerbate disease severity (higher stage), accelerate their rate of attachment loss and decrease their response to our treatment efforts (higher risk).

Making Evidence-based Recommendations

Our patients have a vast armamentarium at their disposal to use in their fight against dental decay and periodontal disease. We should empower them to take control of their oral health to continue our care beyond the dental chair. It is our responsibility to guide our patients toward the use of most evidence-based and effective tools at their disposal. In my office, regardless of the diagnostic state of my patient, I recommend the use of a three-pronged approach to oral home care: oscillating rotating brush, interdental device, and a stabilized stannous fluoride (SnF2) dentifrice. Studies have shown that mechanical biofilm disruption remains the gold standard and is achieved safely with patients using oscillating-rotating electric toothbrushes and interdental devices.9 SnF2 dentifrices offer a distinct advantage over traditional sodium fluoride toothpastes as they can reduce metabolic production of bacterial toxins10, suppress pathogenic virulence11, and promote bacterial and host symbiosis.12

The therapeutic effects of SnF2 were best demonstrated by Biesbrock A et al. who demonstrated 3.7X better odds of shifting from gingivitis to health vs. a negative control sodium fluoride (or MFP) toothpaste using Crest’s SnF2 formulation.13

The synergists effects of using an oscillating rotating smart electric brush, stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice, 0.07% cetylpryidinium chloride (CPC) mouthwash and floss was also highlighted by a 100% transition of gingivitis patients into clinical health after a 12-week trial (Figure 3)14.

Conclusion

Patients will fail to benefit from our in-office restorative, prosthetic and periodontal treatments if there is inadequate home-care routine between their recall and re-care appointments. Dentists, dental specialists, and dental hygienists must work together across the dental profession as an “allied care team” to educate and motivate our patients on effects of patient behaviours and poor home care on their oral health.

References:

1. Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89 (Suppl 1):S74–S84.

2. Berglundh T, Armitage G, et al. Peri-implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S313–S318.

3. Fine DH, Patil AG, Loos BG. Classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S103–S119.

4. Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S159–S172.

5. Lang NP, Bartold PM. Periodontal health. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S9–S16.

6. Murakami S, Mealey BL, Mariotti A, Chapple ILC. Dental plaque–induced gingival conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1): S17–S27.

7. Papapanou PN, Sanz M, et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of Workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S173–S182.

8. Bartold PM. Van Dyke TE. Periodontitis: a host-mediated disruption of microbial homeostasis. Unlearning learned concepts. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:203–217.

9. Vandekerckhove, B., Quirynen, M., Warren, P.R. et al. The safety and efficacy of a powered toothbrush on soft tissues in patients with implant-supported fixed prostheses. Clin Oral Invest 8, 206–210 (2004).

10. Cannon M, Khambe D, Klukowska M, Ramsey D, Miner M, Huggins T, White DJ. Clinical effects of stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice in reducing plaque microbial virulence II: Metabonomic changes. J Clin Dent 2018;29:1–12.

11. Klukowska M, Haught JC, Xie S, Circello B, Tansky CS, Khambe D, Huggins T, White DJ. Clinical effects of stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice in reducing plaque microbial virulence I: Microbiological and receptor cell findings. J Clin Dent 2017;28:16-26.

12. Tao et al. Assessment of the Effects of a Novel Stabilized Stannous Fluoride Dentifrice on Gingivitis in a Two-Month Positive-Controlled Clinical Study. J Clin Dent. 2017 Dec;28(4 Spec No B): B12-16.

13. Biesbrock A, et al. The effects of bioavailability gluconate chelated stannous fluoride dentifrice on gingival bleeding: Meta-Analysis of eighteen randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Periodontology; December 2019.

14. Adam R, Grender J, Timm H, Qaqish J, Goyal CR. Anti-Gingivitis and Anti-Plaque Efficacy of an Oral Hygiene Routine including Oral-B iO Oscillating-Rotating Electric Toothbrush, Stannous Fluoride Dentifrice, CPC Rinse and Floss: Results from a 12-week Trial. P&G Data on file.

![[EN] - Generic Page - Implementing the AAP/EFP periodontal classification image layout 2](http://images.ctfassets.net/nglyjmvvpp62/1ve1rcLzf0rn7nFR17ko5t/1febdb80b08162ca8b072aca8d9dee14/pgoca211246_kol_article_1__hassanpourthe_2018_aapefp_classification_of_periodontal__periimplant_dise.jpg)